The day we moved into the house in Westfield, N.J., several neighbors dropped by to welcome us. One brought her son, Jeff, who was Tory's age. The two hit it off immediately and ran off to play while the movers did their thing.

I had taken the week off to help the family get settled into the new house and, the next day, Judy and I walked the kids to their new school for the first day of classes.

We were there waiting for them when school let out for the day. Tory, all excited, ran up and said, "Jeff invited me to his house. Can I go?"

Thinking it was the Jeff we had met the day before, whose family lived two doors away, we said, "Sure, have fun."

We had been talking with another neighbor and, as Tory began to run toward his new friend, she said, "Wait. That's not the Jeff that lives on our street."

It turns out we were about to send our six-year-old off with a kid we didn't know to a home we didn't know. And Tory had not yet learned his new address or phone number. It could have been disastrous if that neighbor had not spoken up.

We were immediately very cozy in the new house and, after I made my first few commutes to New York City by express bus and my first trip to Newark airport for a flight to a race venue, I felt pretty comfortable, as well.

Meanwhile, the rent/mortgage payments from the Cleveland house arrived like clockwork _ for the first two months. The third payment came in the middle of the month and the fourth payment never arrived.

I tried calling the house numerous times to find out what was going on, but nobody answered and my messages were not returned.

It wasn't very pleasant making two mortgage payments with no money coming in from Cleveland. I didn't know what to do but, as usual, Judy saved the day.

She suggested I call the realtor, Mike. My first response was something like, "Why? He's no longer involved since the house was supposedly sold."

But Judy insisted.

"He's there in Cleveland and, if nothing else, he could drop by and see what's going on," she said.

Expecting little help, I telephoned the realty company. When Mike came to the phone, he sounded nervous.

"Hey, I was planning to call you today," he said.

"Do you know what's going on with our house? We haven't been getting paid," I told him.

"Well," he started, sounding embarrassed, "the husband walked out and the wife couldn't afford to keep the house on her salary."

"Why haven't I heard about this before?" I asked.

"Well," he said haltingly, "we're together now and I didn't want to call you until I could get the situation resolved. But the good news is we've got a buyer for the house. They're going to pay full asking price and we'll pay you what we owe you."

I sat on the other end of the phone stunned. But, in my mind's eye, I could see the young, handsome Mike and the very pretty young wife as a couple.

Again a serendipitous, and totally unexpected, turn of events.

The sale went through without a hitch and I got a check the next week. Coincidentally, Judy's mom was in Westfield for a visit.

I happily wrote her a check to pay back the $20,000 down payment money, with interest. She smiled, thanked me and tore it up.

"Put it toward the children's college fund," she said.

I was obviously living under a lucky star.

One thing that wasn't great about living within commuting distance of the New York office was that I had to go into the city for regular shifts when I wasn't covering a race.

After a while, Judy began complaining that "The AP is taking you away for 35 weekends a year for races and making you go into the office the rest of the time. It's not fair to me and the kids."

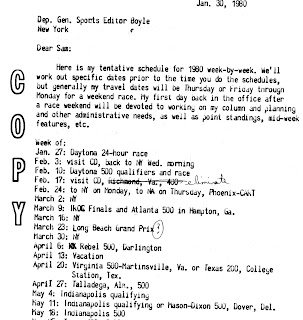

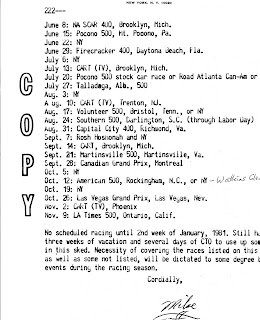

My immediate boss at the time was deputy sports editor Terry Taylor, who later became the AP's sports editor, the first and only woman to hold that position. Terry did the scheduling and pretty much ran New York Sports at the time.

I asked Terry if we could have lunch together on one of my New York days so I could bring up something that was bothering me. The next week I found myself sitting across from her intimidating presence in a cafe in Rockefeller Center.

"Is there a problem?" she asked.

I explained the situation, hoping that I didn't sound like I was whining. Terry sat quietly for a few moments before replying.

"I think Judy is right," she said. "Tell you what. I'll take you off the schedule if you'll agree I can call you in when I absolutely need you."

I quickly agreed.

Terry, who was without question the best boss I ever worked for, lived up to the agreement, calling me in only when she needed a temporary replacement for a staffer who had a heart attack and one other time when she was a staffer short for a couple of weeks.

I did volunteer most years to work in the office over the Christmas and New Year's holiday weeks. The holiday pay was good, the city was alive and fun and the office was usually pretty calm. And I loved standing in the office window looking down at the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree and the crowd of tourists.

As Jews, we didn't celebrate Christmas and, on New Year's Eve, when they were older, I alternated bringing Tory and Lanni into the city with me so they could enjoy the Times Square celebration. Each was allowed to bring a friend along and hang out in the office until near ball-dropping time.

I started covering auto racing at what I think was the start of a golden age, two decades of rising interest and importance.

Within several years, it became a year-round beat, keeping me on the road 40 weeks each year. That was tough on me and on the family. I missed a lot of family occasions, school and scouting events and more.

As I approached the end of my first year on the beat, I was really beginning to enjoy the work and even the travel. But I kept thinking there had to be a way to incorporate the family more.

I broached an idea to Judy. How about going on the road as a family for the nine weeks between the end of school and the beginning of the next year's classes?

After checking out the schedule, I knew we could easily drive between venues most of the summer. And the one or two races that I needed to fly to, I figured we could get one of the moms to take the kids and Judy could go with me.

She loved the idea and suggested that we could help pay for her and kids to accompany me by renting the house for two months.

My first reaction: "You can't do that. Who rents a house for two months?"

But, as usual, Judy was right on. She called the realtor who had sold us the Westfield house and he said, "Sure, we do executive rentals all the time. It's people who are building a house or looking for a nice place to live while they house hunt."

Starting in 1981 and each year through 1991, we traveled each summer in our Pontiac station wagon with the clam shell top, covering thousands of miles.

Each year, Judy would have the kids pick out books to read and a language or some other subject to study as we rode. Since she usually didn't know the languages or the other subject matter that the kids brought along, Judy would learn a lesson one day and teach it the next.

One summer, Judy and Tory "read" a German Mickey Mouse comic book and Lanni studied a Spanish book. Judy always had two-way dictionaries on hand. Each of the kids would spend time in the front seat as they did their learning - and I learned a lot, too, as I drove and listened to the lessons.

We all also enjoyed the Encyclopedia Brown kid detective series that Judy read aloud on the trips in the early years. Turned out it was a highlight of our day.

In the early years of the summer trips, Judy and Kids found things to do during the day when I was at the track, wandering through the various cities and towns we stayed in. As the kids got older, they started going to the track with me and making themselves useful in the media centers and press boxes and giving Judy alone time to study and relax.

Judy and I were both sad when Tory, about to turn 16, decided he wanted to stay home to spend a summer with his friends and find a part-time job. But those trips made a huge difference in our lives, giving us time together when I would have been away from the people I love most.

We always did what we could to make my job work for the family. And the things we did were usually fun for all of us.