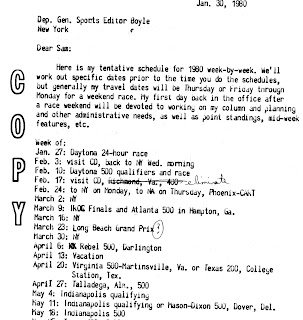

The deputy sports editor in AP's New York Sports department was Sam Boyle. We met on my first day in the New York office and he told me I needed to produce a personal racing schedule for 1980 that could be approved by him and sports editor Wick Temple.

I found it more than a little daunting when I sat down at the typewriter and began to put down my tentative schedule on paper. In my head, race-by-race, it hadn't seemed so long and difficult. On paper, it was nearly overwhelming.

But it was also exciting to realize how many new and interesting places I would be going to.

The most difficult part of that schedule for me was the logistics. I hadn't done that much traveling for the AP, and most of what I had done had been set up by someone else.

Besides arranging the travel _ planes, rental cars and hotels _ I also had to make sure that I had a phone installed at each track in the press box and, in some cases, a line in a media center, too.

Each track also required applying by mail for a credential.

Since I hadn't been to most of the tracks, I had no idea where to tell our tech people to put the installations. That meant calling every track to get a contact name and the location information.

Of course, I quickly realized that I would only have to do this part once, since it would likely be the same information in 1981. Still, it was a big job.

With some trepidation, I handed a copy of the tentative schedule to Sam, wondering if he would think I had overstepped.

He glanced at it, tossed it on his desk and said, "I'll pass it on to Wick, but it looks okay to me."

I breathed a sigh of relief and began making the phone calls. I found nearly every person I talked to at the tracks to be pleasant and helpful. It was a great start to my new beat.

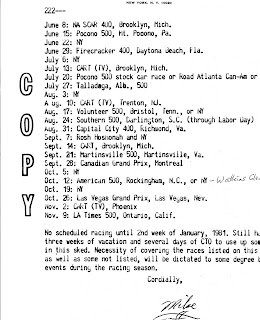

It turned out the schedule really was tentative, with the snow-out at Rockingham necessitating a return trip the following week and the first IndyCar race of the year, scheduled for Phoenix International Raceway, cancelled because of flooding that closed the main road in and out of the track.

There were also weeks later in the schedule when I had to choose between NASCAR or Indycar races. I waited until closer to those dates to see if either race was more important or newsworthy. Sometimes, it was a toss-up and, don't tell anybody, but I usually chose the venue that I was more interested in going to.

Another part of my job was to make sure that the races I didn't cover on the major sanctioning body schedules were also covered, usually by someone from a nearby bureau.

I was back in North Carolina the weekend after the snow-out and, this time, the race went off without any problems. Cale Yarborough won on a cold, blustery day and I came away with a chill from sitting in that unheated press box.

The chill turned into a cold by the time I got back to Cleveland. A couple of weeks later, I saw the PR person from the Rockingham track at the Atlanta NASCAR race and complained to him about his frigid press box.

To his everlasting credit, by the time I attended the October race at Rockingham, there were several space heaters in the press box, including one next to my work area. It was nice and cozy. And I even got some thank yous from several colleagues for opening up my mouth.

The next event was in Atlanta and included a NASCAR Winston Cup race and the finale of the 1979-1980 International Race of Champions (IROC) series.

IROC was a series of all-star events pitting stars from NASCAR, IndyCar (then known as Championship Auto Racing Teams or CART) and road racing in identically prepared Chevrolet Camaros.

The drivers in the finals had made it through three qualifying races in 1979 and then run the first of two final events on the road course at Riverside, Calif.

I had heard of IROC, but I didn't even know what it was until I got to the track and asked a couple of the other writers about it. They raved about the series and also about the husband and wife team that ran IROC.

When I was introduced to Barbara and Jay Signore, it felt like I was like reuniting with a couple of old friends. They couldn't have been nicer or more helpful.

The first thing Barb did was take me around the IROC garage and introduce me to all the drivers, most of whom I had at least met by then.

There were Bobby Allison, Darrell Waltrip, Neil Bonnett and Buddy Baker from NASCAR, Bobby Unser, Rick Mears, Gordon Johncock and Johnny Rutherford from CART, Mario Andretti from CART and Formula One, Clay Reggazoni from F1 and Don Whittington and Peter Gregg from the International Motor Sports Association Camel GT sports car series.

It was a garage full of future Hall of Famers and I had full access to all of them, Talk about a kid in a candy store.

It gave me a great chance to get to know many of them better, and I took full advantage of the situation, hanging around the IROC garage every chance I got.

The driver that I knew the least heading into that weekend was Reggazoni, from Switzerland. He had won five races in F1, including the 1979 British Grand Prix, the first-ever win for Team Williams. For 1980, he had moved to the Ensign team.

Clay was initially a bit shy with me, but warmed up quickly as we talked about family and sports. For some reason, he loved American baseball. When I told him I would be at the U.S. Grand Prix West in Long Beach in two weeks, my first F1 race, he said he would be happy to introduce me to some of the important F1 people.

I was excited to travel to Long Beach, a suburb of Los Angeles. My only previous trips to LA were with the Wisconsin football team for the 1963 Rose Bowl game in Pasadena and earlier in 1980 for the Riverside NASCAR race and the Super Bowl.

But my first look at downtown Long Beach was not what I expected. It was a Navy town and pretty darn seedy.

The front straightaway of the temporary track that wound through the downtown area was on Ocean Boulevard and was lined by palm trees. But the street was also dotted with boarded up stores, tattoo parlors and a XXX movie theater with "Bodacious Tatas" in large black letters on its marquis near the start-finish line.

The media center for the race was in the basement of the new Convention Center, meaning we could watch the race from a media grandstand with no electricity or phone connections or on television from a room with electricity and phone connections but no windows.

I chose to watch on TV and it was a new experience.

Of course, the track PR people brought the top drivers in each session inside to an interview room just down the hall, but it all seemed very artificial.

During the race I also had the "pleasure" of sitting next to a reporter from Germany who broadcast the entire event in his native language over his phone at the top of his voice, trying to make it as exciting as possible even when nothing very exciting was happening on the track. It was definitely an experience.

The best experience of the weekend, though, came when Reggazoni made good on his promise to help me meet some of the important F1 people. Among them was his former car owner Frank Williams.

The team owner from Britain and I hit it off immediately. I asked him about the history of his team and never had to ask another question. He gave me everything I needed for a great, in-depth story about the difficulty of fielding an F1 team. And then he invited me to dinner, and not just any dinner.

His wife's brother lived in Long Beach and had a big dinner at their home each year during the race weekend. It was a beautiful home and a very welcoming group of people.

I was seated between the two Williams drivers, Carlos Reutemann from Argentina and Australian Alan Jones, the eventual 1980 world champion, and across from Frank and his wife. It was an amazing, informative evening.

Long Beach, joining Monaco as the only street races on the F1 schedule, was known to be the toughest and most punishing race of the season for both car and driver.

The start of the race was particularly impressive to this F1 newcomer as the cars zoomed down the front straight, roared past that XXX marquis, braked hard and made a ninety-degree right turn downhill, past the convention center, into the infield portion of the track.

Brazilian driver Nelson Piquet started from the pole and led from start to finish, winning the first of 23 F1 races. But the race was punctuated by several crashes, sadly including one involving Regazzoni.

Clay's brake pedal broke as he raced at 180 mph down the back straightaway and into the track's only hairpin turn. He slammed into Ricardo Zunino's parked Brabham, then hit a tire barrier and careened into a concrete wall. The 40-year-old Regazzoni survived critical injuries but was paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of his life.

That didn't slow him down much, though. The indomitable Swiss driver returned to racing using hand controls and competed in the Paris-Dakar rally and the Sebring 12 Hours in Florida, where we renewed our friendship in the early 1990s.

He later became a commentator for Italian television, but was killed in 2006, ironically, in an auto accident. Clay was 67 years old.

Over the next 30 years I covered just about every Formula One race run in North America, including races in Canada and Mexico. They weren't always easy to cover because I was never an insider and only knew a few key people. But those events and many of the people involved always seemed very exotic to me and I looked forward to them.

No comments:

Post a Comment